Sometimes I truly wonder if certain things happen by fortunate coincidence or if there is some providence involved. Either way, one can truly be impressed at how one little incident can lead to a lifechanging discovery. I may be exaggerating a little, but it still amuses me how impactful this novel was to me, and I probably wouldn’t have even known about it had I not given in to my curiosity. About five years ago, the summer after graduating high school, I was working at a local thrift store in town (fun fact: it’s the store where Napoleon Dynamite got his suit for the dance), and while organizing the movies on the shelf, I discovered a two-cassette video of the 1967 movie ‘Camelot’ starring Richard Harris. I had never heard of it before, and I was curious to see what it was. I could have easily ignored it, but I indulged myself and bought it at closing time for a dollar. It turned out it was a film adaptation of a 1960 musical. It was a fine movie, but I didn’t really have any deep opinions about it.

Last Spring, however, I decided to look up the musical online, and discovered that it was based on ‘The Once & Future King’ by T.H. White, the full collection of short novels published between 1938 and 1940. I read a short article about the book, and I decided I wanted to read it. I didn’t have the opportunity, though, ’til last month (it was checked out by someone else). I had just finished it last Friday, and I’ve got to say it is one the strangest books I’ve ever read. The library stamped it as historical fiction, so I thought it would be more, should I say, down-to-earth from the traditional ballad. Frankly, Merlyn and his magic, and the depiction of the animals such as the fish, caught me by surprise. My first thought was that it was a silly story, but as I kept reading, I came to learn the key themes of the story.

The beginning of the book surprised me not only with its elements of fantasy, but also the kind of fantasy. I was somewhat aware that Merlyn turned the Wart (young Arthur) into animals, though I thought it was more of a hallucination than an actual transformation. But that didn’t matter to the story; what mattered were the lessons that these animals taught the Wart, especially the badger and the geese. They teach him about the nature of man from a different point of view. For example:

“‘The sentries,’ {Arthur} asked. ‘Are we at war?…Are we fighting people?’

“‘Fighting?’ {the Goose} asked doubtfully. ‘The men fight sometimes, about their wives and that. Of course there is no bloodshed–only scuffling, to find the better man. Is that what you mean?’

“‘No. I meant fighting against armies–against other geese, for instance.’

“She was amused.

…”‘Will you stop about it at once! What a horrible mind you must have! You have no right to say such things. And of course there are sentries. There are the jer-falcons and the peregrines, aren’t there: the foxes and the ermines and the humans with their nets? These are natural enemies. But what creature could be so low as to go about in bands, to murder others of its own blood?’“

These lessons would later apply to Arthur as he becomes King. I don’t want to spoil the story (and who doesn’t know that Arthur becomes King?), but I will talk about the themes and certain contents of the story. I’ve come to learn that this novel is more of a satire of the Arthurian legend: some attributes to the original legend are either greatly altered or outright contradictory. For instance, Lancelot is described as being the ugliest of the knights, but at least has the reputation of being the best knight of the Round Table. Much of the book focuses on Lancelot, and his struggles and failures to be the “perfect knight”.

Once I finished the book, I’ve come to really appreciate it. Of course there were some references White would make on human race that are outdated today, but he truly covers the psychology of it in a very provocative manner:

“‘Well,’ said Merlyn, ‘I don’t think he is very different from the others. What is all this chivalry, anyway? It simply means being rich enough to have a castle and a suit of armour, and then, when you have them, you make the Saxon people do what you like. The only risk you run is of getting a few bruises if you happen to come across another knight. Look at that tilt you saw between Pellinore and Grummore, when you were small. It is this armour that does it. All the barons can slice the poor people about as much as they want, and it is a day’s work to hurt each other, and the result is that the country is devastated. Might is Right, that’s the motto. Bruce Sans Pitie is only an example of the general situation. Look at Lot and Nentres and Uriens and all that Gaelic crew, fighting against you for the kingdom. Pulling swords out of stones is not a legal proof of paternity, I admit, but the kings of the Old Ones are not fighting you about that. They have rebelled, although you are their feudal sovereign, simply because the throne is insecure. England’s difficulty, we used to say, is Ireland’s opportunity. This is their chance to pay off racial scores, and to have some blood-letting as sport, and to make a bit of money in ransoms. Their turbulence does not cost them anything themselves because they are dressed in armour–and you seem to enjoy it too. But look at the country. Look at the barns burnt, and dead men’s legs sticking out of ponds, and horses with swelled bellies by the roadside, and mills falling down, and money buried, and nobody daring to walk abroad with gold or ornaments on their clothes. That is chivalry nowadays. That is the Uther Pendragon touch. And then you talk about a battle being fun!’

“‘About three thousand years ago…the country you are riding through belonged to a Gaelic race who fought with copper hatchets. Two thousand years ago they were hunted west by another Gaelic race with bronze swords. A thousand years ago there was a Teuton invasion by people who had iron weapons, but it didn’t reach the whole of the Pictish Isles because the Romans arrived in the middle and go mixed up with it. The Romans went away about eight hundred years ago, and then another Teuton invasion—of people mainly called Saxons–drove the whole ragbag west as usual. The Saxons were just beginning to settle down when your father the Conqueror arrived with his pack of Normans, and that is where we are today. Robin {H}ood was a Saxon partizan.’

“…’And so it comes to this…that we Normans have the Saxons for serfs, while the Saxons once had a sort of under-serfs, who were called the Gaels–the Old Ones. In that case I don’t see why the Gaelic Confederation should want to fight against me–as a Norman king–when it was really the Saxons who hunted them, and when it was hundreds of years ago in any case.’

“‘You are under-rating the Gaelic memory, dear boy. They don’t distinguish between you. The Normans are a Teuton race, like the Saxons whom your father conquered. So far as the ancient Gaels are concerned, they just regard both of your races as branches of the same alien people, who have driven them north and west.’

“‘Uther…your lamented father was an aggressor. So were his predecessors the Saxons, who drove the Old Ones away. But if we were go on living backward like that, we shall never come to the end of it. The old Ones themselves were aggressors, against the earlier race of the copper hatchets, and even the hatchet fellows were aggressors, against some earlier crew of exquimaux who lived on shells. You simply go on and on, until you get to Cain and Abel. But the point is that the Saxon Conquest did succeed, and so did the Norman Conquest of the Saxons. Your father settled the unfortunate Saxons long ago, however brutally he did it, and when a great many years have passed one ought to be ready to accept a status quo. Also I would like to point out that the Norman Conquest was a process of welding small units into bigger ones–while the present revolt of the Gaelic Confederation is a process of disintegration. They want to smash up what we call the United Kingdom into a lot of piffling little kingdoms of their own. That is why their reason is not what you might call a good one.’

“‘I never could stomach these nationalists…The destiny of Man is to unite, not to divide. If you keep on dividing you end up as a collection of monkeys throwing nuts at each other out of separate trees.'” This is my favorite line in the whole book.

“…’He doesn’t care of a fig about Gaels or Galls, but he goes in for wars in the same way as my Victorian friends used to go in for foxhunting or else for profit in ransoms…’

“‘The link between Norman warfare and Victorian foxhunting is perfect…Look at the Norman myths about legendary figures like the Angevin kings. From William the Conqueror to Henry the Third, they indulged in warfare seasonally. The season came round, and off they went to the meet in splendid armour which reduced the risk of injury to a foxhunter’s minimum. Look at the decisive battle of Brenneville in which a field of nine hundred knights took part, and only three were killed. Look at Henry the Second borrowing money from Stephen, to pay his own troops in fighting Stephen. Look at the sporting etiquette, according to which Henry had to withdraw from a siege as soon as his enemy Louis joined the defenders inside the town, because Louis was his feudal overlord. Look at the siege of Mont St. Michel, at which it was considered unsporting to win through the defenders’ lack of water. Look at the battle of Malmesbury, which was given up on account of bad weather. That is the inheritance to which you have succeeded, Arthur. You have become the king of a domain in which the popular agitators hate each other for racial reasons, while the nobility fight each other for fun, and neither the racial maniac nor the overlord stops to consider the lot of the common soldier, who is the one person that gets hurt. Unless you can make the world wag better than it does at present, King, your reign will be an endless series of petty battles, in which the aggressions will either be from spiteful reasons or from sporting ones, and in which the poor man will be the only one who dies. That is why I have been asking you to think.”

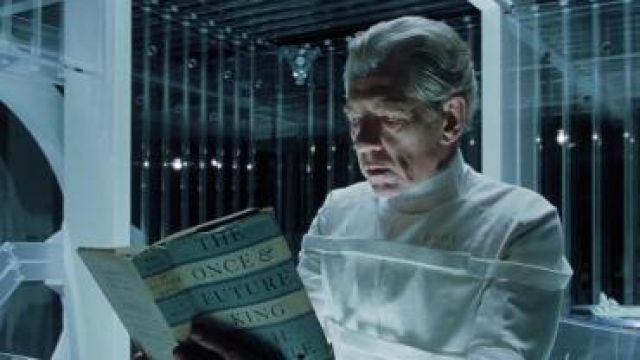

(It’s been revealed that ‘The Once & Future King’ is Charles Xavier’s favorite book, which I think is amazing. Here, in X2, Magnito is reading it in his prison cell.)

White had revised each of his Arthurian novels before putting them together in 1958. What makes this notable is that he was aware he was writing for an audience who had just experienced World War II. I can’t be sure, but I believe he wrote passages like this in direct response to Nazi ideology. When I read this passage myself, I actually cross-referenced this to Hitler’s contrasting view in ‘Mein Kampf’: (See Chapter 1 on his thoughts of Austria and the Reich; see also p. 633-7: Monarchic Patriotism v. National Patriotism)

White even had Merlyn mention Hitler himself:

“‘…There was just such a man when I was young–an Austrian who invented a new way of life and convinced himself that he was the chap to make it work. He tried to impose his reformation by the sword, and plunged the civilized world into misery and chaos. But the thing which this fellow had overlooked, my friend, was that he had had a predecessor of the reformation business, called Jesus Christ. Perhaps we may assume that Jesus knew as much as the Austrian did about saving people. But the odd thing is that Jesus did not turn the disciples into storm troopers, burn down the Temple at Jerusalem, and fix the blame on Pontius Pilate. On the contrary, he made it clear that the business of the philosopher was to make ideas available, and not to impose them on people.'”

I’ve come to realize that this book depicts fantasy in my favorite sort of way. I’ve mentioned earlier that one of my intentions to writing fantasy is to teach my readers how to handle reality, not to escape from it. T.H. White does this very thing, particularly through Merlyn. According to White, this famous magician ages backwards.; the future is the past for him and the past is the future. That is why he can reference events from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The biggest difference I have in my books is that some of my characters, such as Trihan and Vesuvius, know “our reality” as a foreign world, rather than in the future.

The primary theme White expresses, the psychology of war and racism, is my favorite aspect of his book, as I intend to express similar themes throughout ‘The Tales of Draco’, and his final chapter in ‘The Candle in the Wind’ really brings it together:

“{Arthur} had been taught by Merlyn to believe that man was perfectible: that he was on the whole more decent than beastly: that good was worth trying: that there was no such thing as original sin… …he had been destined…against Force, the mental illness of humanity. His Table, the idea of Chivalry, his Holy Grail, his devotion to Justice: these had been progressive steps in the effort for which he had been bred…Might–to have ended it–to have made men happier. But the whole structure depended on the first premise: that man was decent.”

“…During the earliest days before his marriage he had tried to match its strength with strength–in his battle against the Gaelic Confederation–only to find that two wrongs did not make a right. But he had crushed the feudal dream of war successfully {by introducing Total War}. Then, with his Round Table, he had tried to harness Tyranny in lesser forms, so that its power might be used for useful ends. He had sent out the men of might to rescue the oppressed and to straighten evil–to put down the individual might of barons, just as he had put down the might of kings. They had done so–until, in the course of time, the ends had been achieved, but the force had remained upon his hands unchastened. So he had sought for a new channel, had sent them out on God’s business, searching for the Holy Grail. That too had been a failure, because those who had achieved the Quest had become perfect and lost to the world, while those who had failed in it had soon returned no better. At last he had sought to make a map of force, as it were, to bind it down by laws. He had tried to codify the evil uses of might by individuals, so that he might set bounds to them by the impersonal justice of the state…And then, even as the might of the individual seemed to have been curbed, the Principle of Might had sprung up behind him in another shape–in the shape of collective might, of banded ferocity…He had conquered murder, to be faced with war. There were no laws for that.”

“…Man must be ready to say: Yes, since Cain there has been injustice, but we can only set the misery right if we accept a status quo. Lands have been robbed, men slain, nations humiliated. Let us now start fresh without remembrance, rather than live forward and backward at the same time. We cannot build the future by avenging the past. Let us sit down as brothers and accept the Peace of God.

“Unfortunately men did say this, in each successive war. They were always saying that the present one was to be the last, and afterwards there was to be a heaven. They were always to rebuild such a new world as never was seen. When the time came, however, they were too stupid. They were like children crying out that they would build a house–but, when it came to building, they had not the practical ability. They did not know the way to choose the right materials.”

“…the nations and the classes and the individuals were always crying out ‘Mine, mine,’ where the Church was instructed to say ‘Ours.’

“If this were true, then it would not be a question only of sharing property, as such. It would be a question of sharing everything–even thoughts, feelings, lives. God had told people that they would have to cease to live as individuals…God had said that it was only the men who could give up their jealous selves, their futile individualities of happiness and sorrow, who would die peacefully and enter the ring. He that would save his life was asked to lose it.”

“…Perhaps war was due to fear: to fear of reliability. Unless there was truth, and unless people told the truth, there was always danger in everything outside the individual. You told the truth yourself, but you had no surety for your neighbour. This uncertainty must end by making the neighbour a menace…”

“Suspicion and fear: possessiveness and greed: resentment for ancestral wrong: all these seemed to be a part of it. Yet they were not the solution…”

Arthur reflects on these thoughts as his castle is being bombarded. He summons a page:“‘Tom of Newbold Revell…We seem to have involved a lot of people. Tell me, Tom, what do you intend to do tomorrow?’

“‘I shall fight, sir. I have a good bow.’

“‘And you will kill people with this bow?’

“‘Yes, my lord. A great many, I hope.’

“‘Suppose they were to kill you?’

“Then I should be dead, my lord.'”

“‘Could you understand if I asked you not to fight tomorrow?’

“‘I should want to fight’…

“‘Everybody wants to fight, Tom, but nobody knows why. Suppose I were to ask you not to fight, as a special favour to the King? Would you do that?’

“‘I should do what I was told.'”

“‘For some reason, things went wrong. The Table split into factions, a bitter war began, and all were killed.’

“‘No,’ {the boy said}, ‘not all. The King won. We shall win.'”

“‘Everybody was killed…except a certain page…'”

“‘This page was called young Tom of Newbold Revell near Warwick, and the old King sent him off before the battle, upon pain of dire disgrace. You see, the King wanted there to be somebody left, who would remember their famous idea. He wanted badly that Tom should go back to Newbold Revell, where he could grow into a man and live his life in Warwickshire peace–and he wanted him to tell everybody who would listen about this ancient idea, which both of them had once thought good. Do you think you could do that, Thomas, to please the King?’

“…’I would do anything for King Arthur.’

“‘That’s a brave fellow. Now listen, man. Don’t get these legendary people muddled up. It is I who tell you about my idea. It is I who am going to command you to take horse to Warwickshire at once, and not to fight with your bow tomorrow at all. Do you understand all this?'”

“‘Will you promise to be careful of yourself afterward? Will you try to remember that you are a kind of vessel to carry on the idea, when things go wrong, and that the whole hope depends on you alive?'”

“{Arthur} remembered the aged necromancer who had educated him–who had educated him with animals. There were, he remembered, something like half a million different species of animal, of which mankind was only one. Of course man was an animal…And Merlyn had taught him about animals so that the single species might learn by looking at the problems of the thousands…The fantastic thing about war was that it was fought about nothing–literally nothing. Frontiers were imaginary lines. There was no visible line between Scotland and England, although Flodden and Bannockburn had been fought about it. It was geography which was the cause–political geography. It was nothing else. Nations did not need to have the same kind of civilization, nor the same kind of leader any more than the puffins and the guillemots did. They could keep their own civilizations…if they would give each other freedom of trade and free passage and access to the world. Countries would have to become counties–but counties which could keep their own culture and local laws. The imaginary lines on the earth’s surface only needed to be unimagined. The airborne birds skipped them by nature. How mad the frontiers had seemed to Lyolyok {the Goose}, and would to Man if he could learn to fly.”

“There would be a day–there must be a day–when he would come back to Gramarye with a new Round Table which had no corners, just as the world had none–a table without boundaries between the nations who would sit to feast there. The hope of making it would lie in culture. If people could be persuaded to read and write, not just to eat and make love, there was still a chance that they might come to reason.”

One interesting fact about this is that the page was meant to be Thomas Malory, who wrote ‘Le Morte d’Arthur (The Death of Arthur)’ in 1470. White based his book off Malory’s work.

You can sum up White’s message with one simple phrase: “Might is NOT Right”. It was especially appropriate considering it was written in a world suffering from war and fear. It’s still appropriate today, and it has been since Cain slew Able, as White puts it. As you can see, ‘The Once & Future King’ is not escapist fantasy; it deals with subjects all too familiar to us. It’s literature like this that clings to future generations. Scholars study works like White’s to find wisdom that does not change even through the passage of time.

All these thoughts have come to me after reading this book; and I probably wouldn’t have ever read it had I not worked at that thrift store five years ago and decided to buy a video for a dollar simply out of curiosity. Is this the butterfly effect? Is this a fortunate coincidence, or is it providence?

– If you liked this post, please be sure to check out my books listed below. Thank you. Rise of the Dragon from The Tales of Draco – book one (click here) The Six Pieces from The Tales of Draco – book two (click here) Fairy Tales, Fables & Other Short Stories – Collection 1 (click here) Fairy Tales, Fables & Other Short Stories – Collection 2 (click here)